Personal Infrastructure

go to repodocker

Preamble and Motivation

This website had previously been hosted on AWS, in an S3 bucket. Some other projects of mine, too, were hosted on external services. I have come to dislike this centralising aspect of the internet, where so much of what we do is highly dependent on proprietary services run by large companies like Amazon (questions of the ethical positions of these companies notwithstanding). Therefore I had, for some time, wanted to run my own infrastructure in a way that is portable across providers.

There are other reasons for wanting to run one’s own infrastructure, but there are also many caveats. Cost is certainly not a motivator, as running my own server (as a droplet in DigitalOcean’s London datacentre) is more expensive than having my projects in various AWS containers. Convenience is also not a factor, since getting all this working has involved significant pain, many hours of my holidays and evenings, and a lot of learning.

For me there are three prongs to this. The first is control: running everything inside my own system allows me to have fairly fine grained control over every aspect. If I no longer like a particular programme or solution, I can swap it out for another. I also have absolute control over the configuration of these solutions. The second is experimentation: running this myself has meant a great opportunity to experiment with programmes and technologies I would otherwise not get a chance to play with, which then informs other ideas that I have for projects (both personally and for my company). The third prong is ideological: I like open-source software, and I like the decentralised and open internet. It is certainly a bit utopian, but my dream is for there to be millions and millions of tiny collections of software, run by individuals for their own use, and sometimes the use of small collectives, but never dominated by big, proprietary systems.

General setup

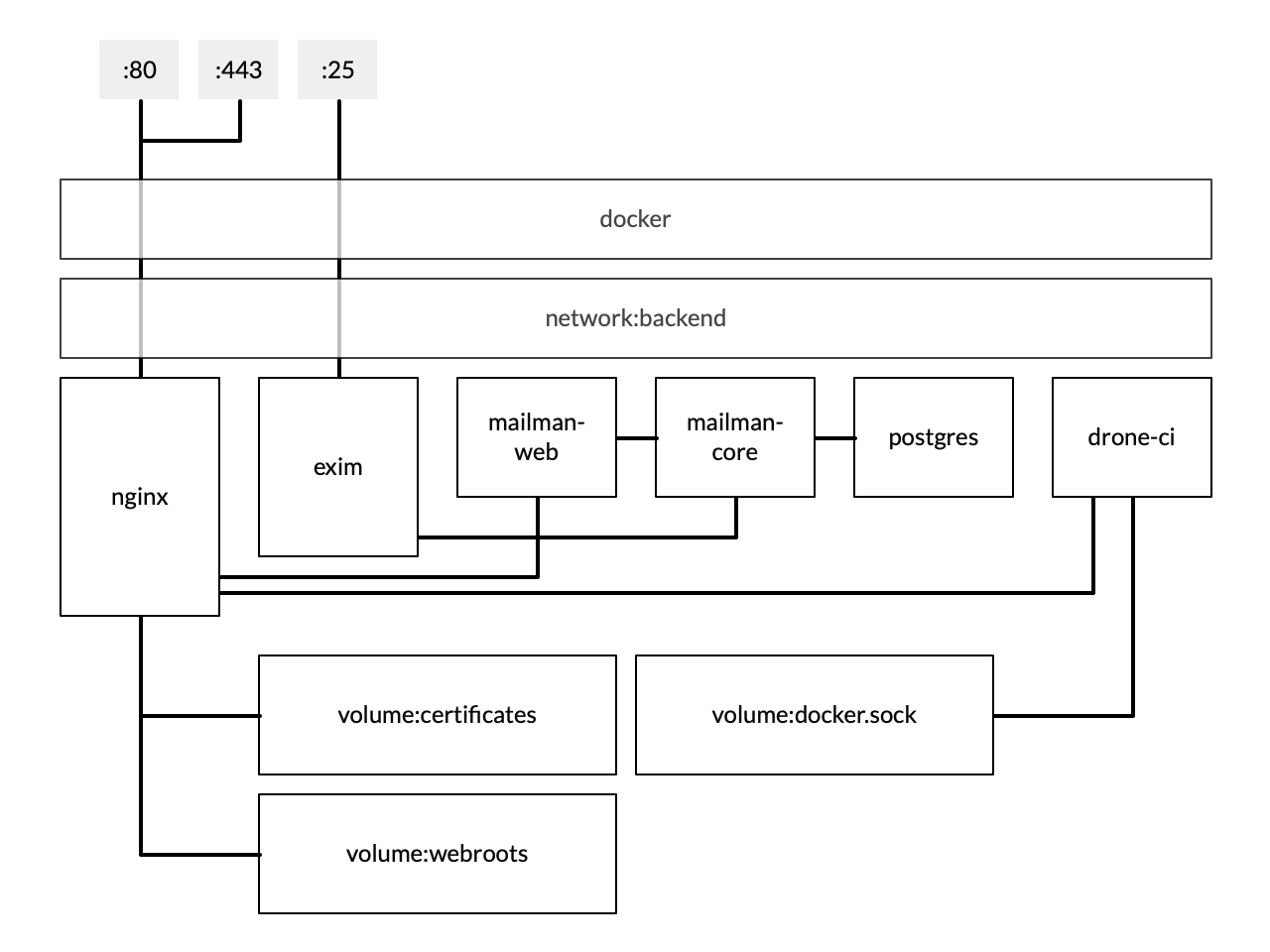

The project centres around configuration for docker-compose, which defines a number of services, volumes, and networks. The nice thing about the way in which docker-compose works is that the internal networks mean I can link services together very easily without ever exposing them to the host or the wider world.

Most of the services expose some sort of web frontend. In order to make HTTPS setup painless, I decided to just front everything with an nginx reverse-proxy. Then, through the magic of docker, all the services can be exposed indirectly (without ever being directly accessible by the outside world), and I can handle my SSL certificates using LetsEncrypt and certbot.

Mailing lists

The project which kicked me into action was one in which I wanted to setup my own mailing lists. I go to see a lot of theatre, dance, art, talks, &c., and I often find myself copying tens of email addresses into the To: field of my email client, while trying to work out if I have missed anyone out. I wanted an easy way of sending out a list of things I am going to see, to find out who else amongst my friends and family are interested so we can go together.

I used GNU mailman, with which I was familiar as a user from my time at Cambridge – most of the societies ran on the SRCF’s infrastructure, including using their mailman instance for the countless hundreds (thousands?) of mailing lists that there were.

This was far from straightforward to get working. Thankfully some of the work had been done for me, and a set of docker images for mailman had been created. Configuring these, however, could be a bit of a mystery, and email is very hard to debug. To date, in fact, I’m still not confident that the setup is completely working (for example my archives are empty, no matter how many emails I send).

The most complicated part of this was setting up exim, which is a well-established MTA recommended by the mailman documentation.

Exim is complicated because it is extremely configurable, but the configuration is really hard to understand if you have never really had to interact with an MTA before. The exim documentation is actually quite good, but very hard to parse for a newcomer. There was a lot of head-against-brick-wall going on, but I had a bit of a breakthrough when I realised that the reason that my emails weren’t being delivered to mailman was that the router was too low a priority, and that the configuration wasn’t being properly incorporated anyway. I suddenly understood the relationship between emails, routers, transports, and access-control lists.

Once email was actually being delivered, I had another problem, which is that almost as soon as my MX records were published for the mailing list domain, my poor exim instance was being abused by spammers to relay spam (I had inadvertently set up an open-relay). I eventually setup an access-control configuration which allows anything to any recipient if the source is on the local docker subnet, and allows any host to send emails to my mailing list as long as the sender and sending host are verifiable (SPF, DKIM, etc.). Unfortunately for my poor server, Google has blacklisted me (as, I’m sure, have others) and there is little recourse to this except to wait until my bad reputation subsides.

Exim has some very nice debugging features to help with setup. For example, to understand how routing and transports worked, I could check what would happen to an email destined for a particular address using:

exim -bv -d+all my.list@my.domain.tld

When I was trying to test my access-control lists, I could simulate an SMTP exchange with a spoofed host address using:

exim -bh XX.XX.XX.XX

So when I was trying to see what would happen if I sent emails from the local subnet vs. a gmail server, I could try the following SMTP exchange using the different host addresses:

EHLO mx.somedomain.com

MAIL FROM: spammer@gmail.com

RCPT TO: spammee@gmail.com

My mailman/exim setup now works, and I also had to setup DKIM and SPF to make it less likely that I will get marked as spam. The spf records were relatively easy, although required some tweaking to get right and DNS updates are not instantaneous. For all of this I found the mxtoolbox “SuperTool” extremely helpful, as well as this guide on using DKIM in exim. I finally had to move my DNS over to DigitalOcean so I could have the PTR records corresponding to the right domain.

Web hosting

In order to provide a web endpoint for my website, any other projects I want to release publicly, and also the various services that form part of this infrastructure, I am using nginx running in its own container. Using nginx to front all web requests means it is also very easy to have SSL working for each endpoint, regardless of the vagaries of configuring each individual service to use SSL. I’m using LetsEncrypt for my certificates, with certbot to handle the ACME challenges.

To do this, each service has two server blocks. The first listens on :80 (HTTP), and performs two functions: firstly, it provides access to the ACME challenge files to validate the domain with LetsEncrypt, and secondly it provides a redirect from HTTP to HTTPS for everything else. The second server listens on :443 (HTTPS) and provides a reverse-proxy for the underlying service. This had to be configured in different ways depending on what we are fronting: for mailman-web we provide a uwsgi proxy, whereas for drone-ci we provide a simple reverse-proxy. The nginx container mounts two volumes, one for webroots and another for certificates. certbot can then just add files to the <service>-acme webroot, which is served from http://<service-name>.gtf.io:80/.well-known, and then dumps the certificates in the second volume and has a deploy hook to restart the nginx container.

CI/CD

Initially I tried to use Jenkins as a CI server, and initially it seemed simple to set up, but eventually trying to get it to work with docker containers internally so I could build within those containers was painful. Jenkins is clearly quite powerful, and I had used it before many years ago, but it feels like it has so much legacy that it is ill suited for modern CI/CD methodologies. This opinion could be completely incorrect, and I could have been doing something stupid, but I got frustrated with trying to get it to work and so opted to test something I had only just discovered: Drone.io. Drone was very easy to setup, and almost worked out of the box, except that it just was not receiving push events from github. The documentation is quite spare, and so it took some research and debugging but I worked out that the webhooks were not making it through to the server. The reason for this was that, since Drone was setup as an HTTP service (as it was being fronted by nginx), it was configuring the webhook to go to hit http://<domain> rather than https://<domain>. This meant that it was encountering a 301

redirect which it wasn’t following. Fixing this fixed the problem.

I am not sure I will stick with Drone in the long run, as it really lacks any configuration options. It’s default position is to allow anyone to sign up, and working out how the access control works is a little mysterious (I have set a list of allowed users, but have no idea if this works or not). It does have a nice CLI tool, which was the only way I found to rebuild a failed build at first (quite frustrating really).

There are some other alternatives I would quite like to try, like TeamCity and Concourse but those are for another time.