Content, Creativity, and Monetisation in the Modern Internet

, 2024 words

I miss the Old Internet. I miss the terrible flash games, raw vlogs, websites with bad styling and unpolished content. This is despite the fact that they were overloaded with visual noise — full of pictures, marquee text, and design decisions that should never have seen the light of day — and were much more limited in functionality. When comparing to what we have now, where I can access a smorgasbord of media, journalism, and services, the early web was ugly, difficult to use, and lacked much of the utility that today we take for granted.

In reality, this nostalgia for the internet of my teenagedom is not really about a direct comparison of the quality of the content1. It is really about what we have steadily lost in the modern era of highly monetised, polished, and carefully tuned content creation.

When the web started to be more widely adopted, and blogs started to be published (normally the work of just a single author) in the 1990s, it was an amazingly egalitarian platform. It was not democratic in all dimensions as it required some technical knowledge to successfully run a website, not to mention the hardware and infrastructure that was unavailable outside wealthier areas in wealthy countries. The lack of any dominant content platforms like YouTube and Medium2, however, meant that there were no gatekeepers, and no platform owners who could change the rules. No-one was there to make rulings on what could and could not be published, what would and would not be seen.

Hyperlinks between documents stored on servers allowed users to discover a wide range of content produced by a diversity of people who had no particular affiliation to one another. Those hyperlinks were not created by consensus, or by a publisher, but by the individual content creators themselves. As such it was possible to discover a whole realm of content without any directing force. This is what made the web what it was, and such ideas are under threat both from the stupidity of legislators 3 and our own forgetting, thanks to the ubiquity of publishing platforms which seek to keep users within their walls.

These platforms have had some positive social impacts, for example circumventing authoritarian governments as with Twitter in Iran. In the context of a mostly free society, however, their (increasing) editorial control and ubiquity threatens the creativity and freedom of the web. There is also an increasing trend of these platforms capitulating to the demands of authoritarian governments4 around the world, making them complicit in locking subjugated populations out of the world of free (as in speech) information.

While the printing press allowed the wide dissemination of material to consumers outside of elite control, the early web completed the other side of this process, opening up content creation to anyone with a terminal (or a nearby internet café). Internet cafés in particular were like the libraries of the early web — not everyone could afford their own, but many people could afford to gain some access through a communal service5 (although this was not globally true).

The audiences of the printing press and early web were, on the face of it, quite dissimilar. The printing press allowed the dissemination of material embargoed by those in power (mostly the Church), for example English-language bibles. By contrast, the early internet was not primarily used as a method of circumventing content bans amongst dissenters (although there was a certain degree of this, for example with the sharing of hard-to-access or copyrighted material). What these did have in common, however, was that they were being used to distribute content amongst consumers in a non-commercial sense — this was information production and consumption for the sake of the information, rather than for a financial model.

The result was a wild and anarchic jumble of content, often heavily experimental spawning a wide variety of subcultures and niche interest groups. Much of the content from this period was relatively unfiltered and very unpolished. The fact that the web was less centralised and that social media had not yet birthed the VirtuMob(TM) meant that people could express themselves more freely and could experiment with ideas and content (which is not to say that there were not a number of moral panics6 and the like).

The web of today is quite a different story. Of course there are still individual blogs (like this one), and it is far from impossible to launch your own content on your own platform as the architecture of the internet has not fundamentally changed from that perspective, but we have seen two worrying trends (one caused by the other). The first is the increasing monetisation of content via advertising on the internet. Some content creators make huge amounts of money7 in advertising revenue. The second trend, related to the first given the advertising model of the internet, is the centralisation of content in a limited number of platforms like YouTube, Facebook, Medium, and even Wikipedia8.

There is a tension here, in that access to publishing (and even the web itself) was much more restricted to the well-off and those with specialist knowledge (like how to host a blog), and access to hardware and infrastructure. In that sense the earlier web was less democratic, but for those who were able to publish and consume content (arguably, therefore, an elite), the web was far more egalitarian. Content was weighted more equally in the absence of data-driven search engines and publishing and dissemination platforms (like Google, Facebook, and Twitter) which control “feeds” of information. This tension is inevitable, as the democratisation or opening-up of the web to increasing numbers of publishers and consumers drove the potential for monetisation, which then decreased the openness and balance of the entire ecosystem. Thus as this open and egalitarian space was “democratised” by being opened up to the wider population, the same features that made is open and egalitarian also created the space and incentives for the platforms that would eventually cause a reversal in this openness and freedom.

Perhaps it is the case that it is only really possible to have freedom of creativity amongst some form of elite or restricted group. This is rather an uncomfortable conclusion but there are some obvious reasons for it. Wider accessibility means that the majority consumer is not in the early-adopter category, and therefore has a different tolerance to new ideas and imperfect content. There is often a sense of snobbery accompanying talk of “mass” or “common” markets, but it seems to be inherently true that anything made for a wider market will both be influenced by primarily economic forces (rather than producers operating according to some other motivator), as well as consumed primarily by those with little patience for the experimental.

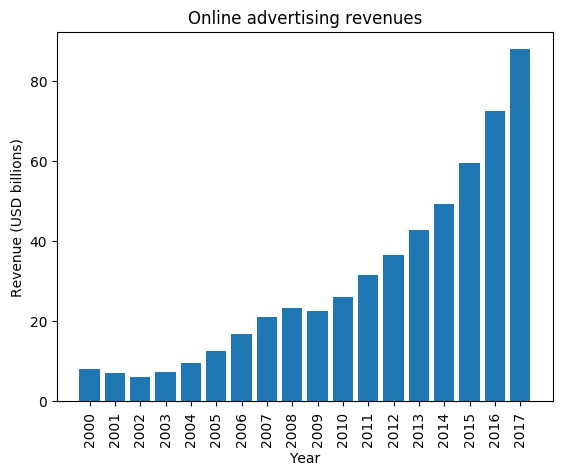

Since 2000, the monetisation of content on the internet has increased massively9, from $8.23B in 2000 to $88B in 2017. The huge increase in advertising revenue over this period could be down to some combination of three factors: increased internet adoption resulting in more views and therefore clicks on adverts; improved advertising technology, providing a higher conversion rate as well as more placement opportunities; and finally, increased awareness and adoption from advertisers resulting in a higher overall budget allocation.

As advertising revenue has increased, there is a resulting increase in the incentive to create content with which to draw users in. This has two results: platform centralisation, and content optimisation and convergence.

Platform centralisation is a fairly obvious effect of this, since dominating the space provides a multiplier effect on the increasing revenue to be gained. This drive towards a monopoly happens in many markets, but the difference in this one is that the market is advertising, whereas the effect is on the content platforms. We expect advertising revenue to support content platforms, but in reality content is merely a hook to provide consumers for advertising.

While the centralisation of these platforms has made it easier for a wider array of people to publish content online (thus increasing the democratisation of the web), it also means that there are a smaller number of gatekeepers of content, and whether a piece of content gets seen by a given user is now dictated by a dwindling number of these gatekeepers. Platforms are heavily incentivised to funnel content that they believe is most likely to keep a user on the platform, thereby generating more advertising revenue, as well as to use psychological tricks10 to keep users engaged11. This is well illustrated by an article in aeon about online pornography12:

Powered by ad revenue, the tube sites felt an economic tug to draw more people to their sites for longer chunks of time. Since they had – at least initially – no control over content creation, the name of the game on tube sites for the past few years was content funnelling.

Similarly, as the platforms centralise and increase the efficacy of their content funnelling, driving increased advertising revenues, content creators are incentivised to produce content that the big data machine suggests will maximise viewership and engagement. The result is that content experimentation and diversity now carries a high cost in terms of lost revenues. Whilst previously there was a cost associated with a “flop”, for example a movie taking in low earnings at the box office, it was much harder to know what would flop and what would succeed. The introduction of large datasets (“big data”) on user behaviour and tastes (although it is difficult to say how accurate the analyses resulting from these datasets really are) has meant that it is now much easier for content creators wishing to maximise advertising revenues to use big data to craft content that is most likely to appeal to their desired audiences.

Where once we would have expected creators to supplement their incomes using advertising, the tail is now wagging the dog in that content creation is being driven by advertising.

Within the context of the web, as content platforms have increased their ubiquity, content creators are very much subject to their control. While one might argue that if the technology is simply doing a more efficient job of matching up what content creators are producing with audience’s tastes13 then it is serving a worthwhile purpose. Before the technology provided such a complete picture (regardless of accuracy) of what might be popular, in the face of such uncertainty, diversity flourished as only with some failures could the successes fall out of the mix. While inefficient in terms of generating popular content, this diversity is important to our culture, as it allows new ideas to grow without being culled too early by a hallowed model of popularity.

There are two pernicious effects arising from this. Since there is not an infinite supply of content, it is impossible to tailor it to each individual’s tastes. Even were it possible, it would be undesirable: if we only ever get what we want, then our worldview will never expand beyond its present confines as we will never be exposed to anything that does not perfectly accord with our own views and tastes14. In any case, by tailoring content to some audience group of size greater than one, we end up promoting certain tastes above others. The result will be groups that converge to a particular set of tastes as they are increasingly exposed to them.

Not only will we have increasingly isolated, intraconvergent groups of consumers of content, the content itself will be converging to the mean for each group. Anything that deviates from the local maxima of engagement for each group will quickly be discarded due to the high rewards from advertising revenues. This has serious implications for our cultural output as society, as we focus increasingly on producing the equivalent of bubble gum for the mind - endlessly chewable, increasingly devoid of flavour, sufficiently sweet but insufficiently anything else, and certainly unlikely to challenge our ideas.

-

By “content”, I mean everything that people produce online, so that could be articles on newspaper websites, blog posts in individual or syndicated blogs, videos on YouTube and Vimeo, imagery from DeviantArt or Instagram, or even Tumblr, and online games.↩︎

-

And, arguably, Google which, while not a platform, has such control over people’s access to content that it could be counted in the same category.↩︎

-

“Oettinger’s copyright reform proposal is unfit for the digital age” (retrieved 2018-12-16)↩︎

-

“Google China Prototype Links Searches to Phone Numbers” (retrieved 2018-12-20)↩︎

-

“The Weird, Sketchy History of Internet Cafes” (retrieved 2018-12-20)↩︎

-

“Brass Eye: Paedogeddon! Special (2001)” (retrieved 2018-12-22)↩︎

-

“This Guy Makes Millions Playing Video Games on YouTube” (retrieved 2018-11-17)↩︎

-

Wikipedia is a very different type of platform, given that it is inherently informational, and there is normally a 1:1 relationship between that for which a user is searching and the articles themselves. It is also not supported by advertising, and is volunteer run. Nevertheless it is worth mentioning as it has become the predominant knowledge repository online.↩︎

-

“IAB Internet Advertising Revenue Report” (retrieved 2018-11-17)↩︎

-

“‘Our minds can be hijacked’: the tech insiders who fear a smartphone dystopia” (retrieved 2018-11-18)↩︎

-

“Ex-Facebook president Sean Parker: site made to exploit human ‘vulnerability’” (retrieved 2018-11-18)↩︎

-

“Micro-targeted digital porn is changing human sexuality” (retrieved 2018-11-18)↩︎

-

Dealing with actual tastes vs. what different audiences want to project to others by virtue of their perceived tastes is somewhat beyond the scope of this essay.↩︎

-

There’s an analogy in the numbing effects of Soma in Brave New World, but it is not an exact one.↩︎